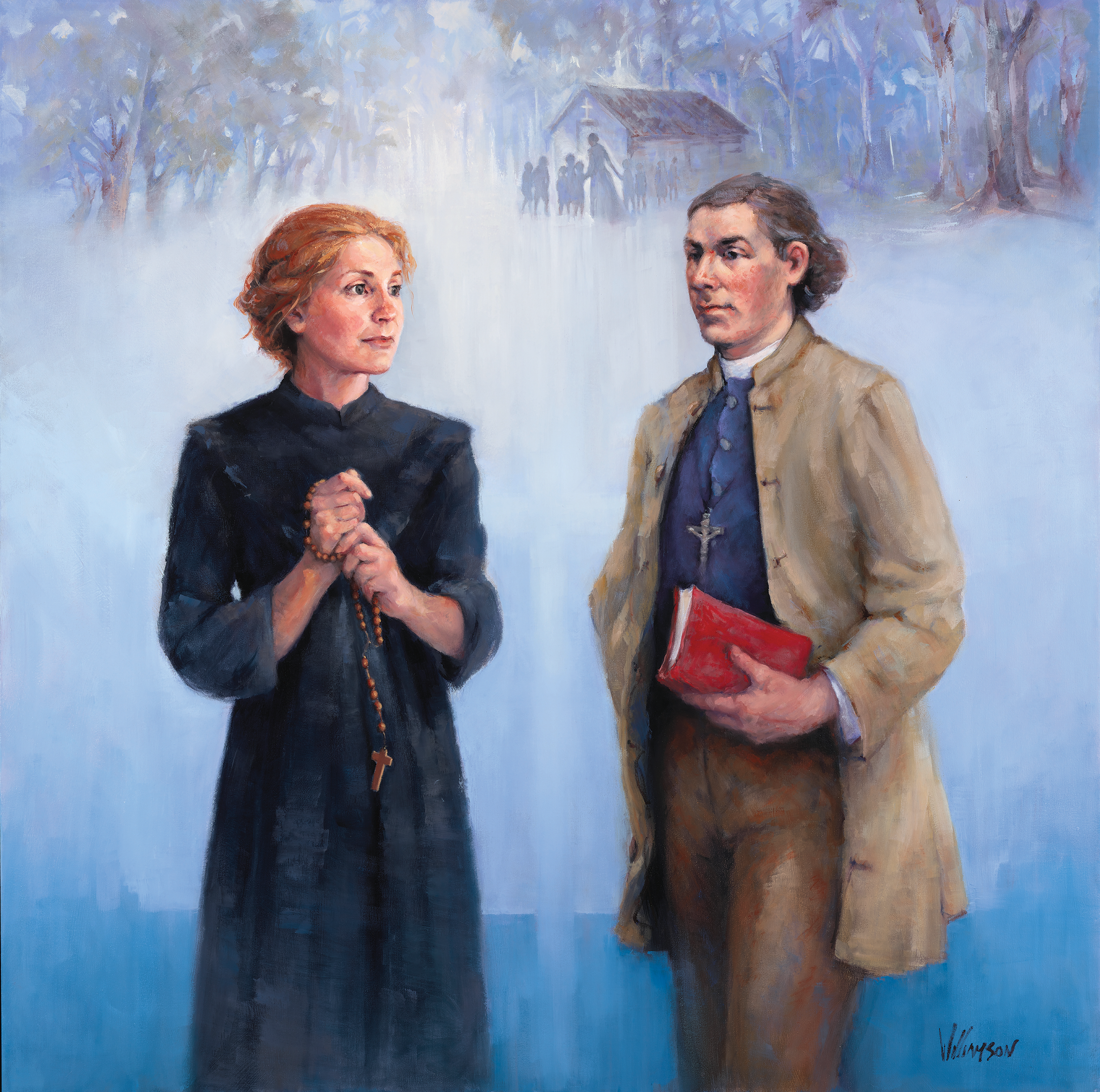

On 31 May 1867, Father Julian Tenison Woods sent to Mary MacKillop the first Rule of the Sisters of Saint Joseph. This became the founding document, encapsulating the vision for the order and providing the Sisters with important guidelines for their ministry.

It had arrived! Here was the fruit of their discussions. Sister Mary MacKillop opened it carefully, her heart filling with joy as she read Father Julian Tenison Woods’ words in his letter of 31 May 1867:

Dear Sister Mary

I enclose the Rule. You must without delay copy it out into a small neat book, smaller than this note paper, and written only on one side and enclose it back to me.

In her hands, Mary held the first Rule for the Sisters of Saint Joseph, their founding document. She was to keep this original and only show it to others wanting to become Sisters.

Although it had only taken him a couple of days to compose the Rules of The Institute of St Joseph for the Catholic Education of Poor Children, Fr Julian had long been “brooding over the establishment of a religious order of teachers”[1] specifically suited to educating the poorer children in the scattered and remote parts of Australia, ever since he had encountered the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Le Puy, France.

His Sisters were not only to teach the poor and provide social welfare, but quite literally to be at home among the poor – enduring the same privations as those they were called to serve. Their convents should be the humblest of dwellings, sparsely furnished and appointed, with straw beds in a common dormitory. Their clothes were to be “of poor material”,[2] their undergarments of unbleached calico. They were to own nothing except their habits and a breviary.

They were not to own any property, not even a Mother House, and the Sisters were not to earn money, but rather to rely on alms or any incidental school fees that parents might be able to pay. Thus, they were to be fully reliant upon God’s Providence.

Like other religious, the Sisters were to wear habits, take a vow of poverty, chastity and obedience, and live in community. But this Australian-born order would be markedly different. The Sisters would not be cloistered, but go out into the community in small groups, perfect for establishing foundations in the scattered Catholic communities. A dowry was not needed to enter nor was a particular level of education required; and there would be no class distinctions among the Josephites. This meant that local ‘colonial girls’, who generally possessed neither wealth nor extensive education, would have the opportunity to join.

The Rule laid out the regulations and duties of daily life, the times for housework and meals, and for spiritual exercises and visitation. But the main emphasis was the education of the children, particularly poor children, so that “they [might] grow up, to live as good and pious Christians”. And this they should do gently, cheerfully and patiently, making themselves “the companions of the children”.[3]

The Rule’s emphasis on central government would go on to be a significant point of tension with the Bishops who favoured diocesan control. But for now, Mary held in her hands the ‘roadmap’ for developing the new order and looked forward to opportunities to “never see an evil without trying how they may remedy it”.[4]

Janette Lange

South Australian Archivist

Footnotes:

[1] Anne Bulger, Memoirs of Reverend J.E. Tenison-Woods, Volume 2, p.24 (dictated 1888).

[2] Rules of The Institute of St Joseph for the Catholic Education of Poor Children, Section III. Of the Habit. (Composed by Father Woods May 1867; approved by Bishop Sheil, 17 December 1868)

[3] Rules, Section VI. Of the Daily Duties.

[4] Rules, Section XIII. Of Novices, Externs, etc.