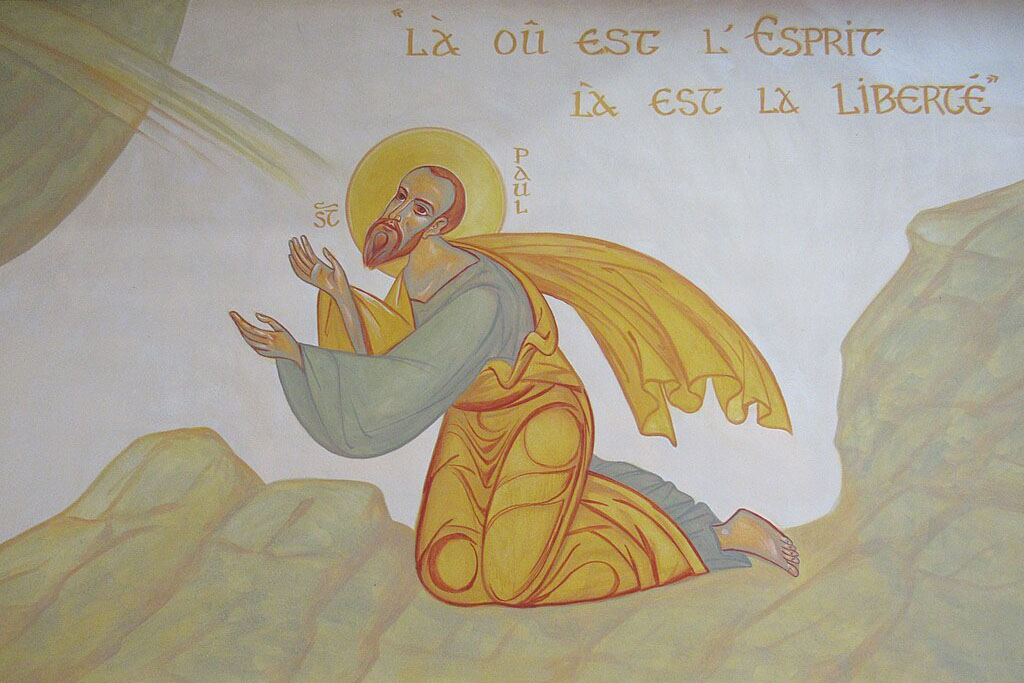

We commemorate the feast of the Conversion of St Paul (previously named Saul) on 25 January annually.

On the road to Damascus, Saul of Tarsus was turned upside down and inside out. Usually referred to as his ‘conversion’, it has been described by one scholar as “the intervention by the risen Christ into Paul’s interior experience which stunned him for the rest of his life”. [1]

The version of events which people usually draw on for insight into this ‘conversion’ is found in the Acts of the Apostles 9:1-25. Surfacing in the late 1st Century or early 2nd Century CE, Acts was written well after the death of Paul in Rome in c. 68 CE, yet it does narrate significant events in the life of Paul and other apostolic missioners in the early Church, and is significant for the ongoing Church’s sense of faith and mission.

Firstly, let us consider ‘Paul’s conversion’ as it is told by others in Acts, then move to reflect on what he says first-hand in his letters about his own experience

According to Acts 9, Saul is a zealous Jew travelling on mission to Damascus, intent on apprehending Jesus-believers who are deemed to be disrupting Israel’s ancestral faith. On the way a blinding light flashes around him causing him to fall to the ground. He hears a voice asking with insistence, “Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting me?” [v 4]. Replying with something like, “It depends who’s asking”, Saul discovers it is the very Jesus whose followers he is persecuting who has interrupted his journey. Jesus then directs the now-blinded Saul to Damascus to meet with a disciple called Ananias. Meantime, Ananias is assured by Jesus that Saul, the persecutor whom he is naturally quite reluctant to meet, is in fact God’s “chosen instrument to bring [Christ’s] name before Gentiles and kings and before the people of Israel”. [v.15]

Saul is led into Damascus, welcomed as ‘brother’ and blessed with the Holy Spirit by Ananias and other disciples. Acts 9 then relates how Saul immediately responds to his life-transforming encounter with Christ and begins to preach powerfully in his name. He draws understandable hostility from Jewish authorities who mount serious plots against his life. Jesus’ disciples help him escape from these. Progressing from then into a life dedicated to Jesus and moving across the Roman world, Saul later begins to use his Roman name, Paul.

If we were to come to this story with a stereotypical mindset on ‘conversion’, we might imagine that Saul could have been gradually sensing a call from God to change his anti-Jesus stance. Were we thinking this way, we might have been tempted to wonder if such a determined persecutor as Saul had ever found himself pondering, “Maybe these Jesus-fellows are right! Perhaps the one they follow is worth following. I’m doing my darnedest to root them out, but they show such bravery and determination. They go to their deaths in defense of him. I’d have to admit they are admirable. Maybe I’m the one who’s wrong!”.

Further scriptural evidence shows that Saul was certainly not ‘converted’ in this way. Writing at least half a century before Acts, in his own wording in Galatians 1:11-12, Paul insists his call has been received directly from Jesus:

Kevin O’Shea insists the word ‘revelation’ is important to take time to explore, being Paul’s preferred word to account for what happened. In Greek it is ‘apocalypsis’, bearing the original sense of ‘apocalypse’, not as a fiery cataclysmic implosion of all reality or a type of Armageddon, as might commonly be imagined, but as the true unveiling of God’s ultimate, eternal will for all reality. Paul’s use of ‘apocalypsis’, says O’Shea, conveys the extraordinary meaning that ‘God has ‘apocalypted’ his Son in me’. Though strange to our ears, it is a powerful statement about Christ, showing Paul’s realisation of all Christ really means for humanity and for all creation.

In Galatians 2:20, Paul articulates this new realisation in these words: “For me to live is Christ”, and in 2 Cor 5:17 he writes of life “in Christ” as a life transformed. For the Christian baptised into Christ’s life, death and resurrection, there is a totally re-worked way of being human, “a new creation; everything old has passed away… everything has become new!” [2 Cor 5:17].

So, Paul teaches in the community of Corinth across 1 Cor 11:17-34, that the Christian community is the ‘Body of Christ’. Within that Body there is no place for arrogant superiority of some people over others, or for competitive, combative division between people who happen to be different from each other. All are equally baptised, teaches Paul, and differences are meant to give rise to the flourishing of varied gifts to which the whole community has a need and a right. Patterns of thinking and norms of behaviour in Roman society must give way to new mindsets and life-habits sparking Christian equality, co-operation and inclusivity.

Early in his ministry from Antioch in 48 CE in Gal 3:27 -28 Paul teaches of this in these words:

In what history has called Paul’s ‘conversion’ his life is tumbled. It is a reality ritualised by the ‘drowning/immersion’ that his ‘baptism’ has wrought in him. This leaves him, as baptism leaves all of us, with a new identity. It would be Paul’s hope that we would also share his unshakeable conviction of the union between Christ and humanity, of which he writes in Rom 8:35, 37-39:

37 No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us. 38 For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, 39 nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Virginia Bourke rsj

[1] In this article I am drawing on the words of Kevin O’Shea CSsR from a series of faith formation lectures in the Maitland-Newcastle Diocese in the Jubilee Year of St Paul in 2008-2009. I participated in these lectures, and I sought and received Fr O’Shea’s personal permission to quote him and draw on his scholarship in my own ministry afterwards. Fr O’Shea has since died.